BWV 999

One of the greatest joys of my life as a musician has been playing music written by J.S. Bach. To play music by Bach is to know, or at least feel the proximity of, the DNA structure of music. As musician Tim Kramer put it, “playing Bach is like musical Yoga.” It does something to you.

BWV 999 was probably written for a now obsolete instrument called the lautenwerck, or keyboard-lute, which was similar to a harpsichord, but with gut-strings, and a sound that was very much like a lute. The earliest known notation for the piece is written in keyboard style, and was originally in the key of C Minor. Most guitarists, myself included, play the piece in the guitar-friendly key of D Minor.

The process of learning a piece by Bach always follows a similar arc for me. The first encounter with a piece feels like a series of lessons. There is something that you are supposed to notice, a first musical clue to lead you into the piece.

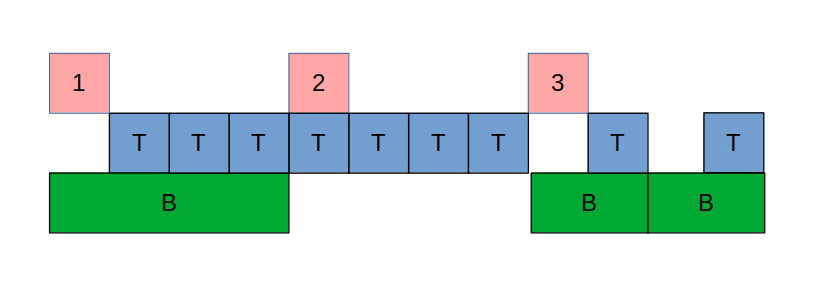

In BWV 999, it was the rhythmic ostinato that first drew my attention. The piece, in 3/4 time, is 43 measures long, and 41 of those measures have an identical rhythm. Each measure begins with a quarter-note in the bass voice (green) and a sixteenth rest in the treble, followed by 7 arpeggiated sixteenth notes in the treble (blue), and ends with alternating bass eighth notes and treble sixteenth notes:

The segmentation of the bass and treble notes invites contemplating the two voices separately.

The treble voice is always an arpeggio of three notes, usually a triad. Starting on beat 3 of every measure, the bass plays three descending notes, sometimes a triad and sometimes other chord tones.

In the first two measures, both the treble and bass voices consist only of notes from the Dm chord, so nothing unexpected.

Measures 3 and 4 move to the vi chord, Gm, but still with the D root. Bach is setting us up for a classic i – iv – V7 – i chord progression, with emphasis on the tonic note.

But when we get to measure 5 and 6, the treble voice shuns the root and sounds the top three notes of the V7 chord, while the bass continues playing the notes of a Gm chord. So what expectation tells us should be an A7 chord has no A, is overlaid on top of a Gm chord, with a D as the lowest note. We’re only 6 measures in and space-time is already starting to melt!

Measure 7 brings us back to the reassurance of the tonic chord, but by measure 8 things are moving again. For the next three measures, the treble voice continues singing the notes of a Dm chord, while the bass note on beat one of each measure moves down by steps, to make Dm/C, then Bbmaj7, before landing on Dm/A. This is the last time we hear the tonic chord until measure 39.

It is interesting to note that many people think it likely that the Beatles song “Because” was inspired by the harmonic movement of this section of BWV 999. Despite “Because” being about half the speed, the similarity is striking.

Measure 11 reminds us it’s Bach we’re dealing with, so we depart the safety of the tonic chord for a jagged G#dim chord, that by the end of measure 12 has transformed into an E7. Measure 13 and 14 are Am9 to Am. Suddenly, it feels like we’re actually in the key of Am, and we’ve just heard a V7 – i cadence.

From there it’s an Fmaj7, followed by a chord you could think of as a Dm#6, but I hear as a G9 without the root, before landing solidly back on E7 again. You don’t need a blow-by-blow of the entire piece to get the idea. Things move around a lot, and notions of what is “supposed” to work in music are tossed out the window.

When I’m first learning a piece by Bach, I often find that the musicality of the piece is difficult to pin down. It feels like first I have to grapple with all the musical puzzles presented, before I can relax into the piece and start to hear to its unfolding beauty. Eventually, the voices of the piece become just that – voices, in a perfectly balanced conversation.

Needless to say, it is one thing to break down the movement of chords on paper and something else entirely to play. When I am playing Bach, I can feel all of the structure inherent in the music, at a speed and depth that is simply too much to ever express with words.

I am pretty much always working on at least one piece by Bach on either guitar or piano, and I don’t think I will ever tire of trying to solve these perfect musical puzzles.

BWV 999 is part of the Royal Conservatory of Music Grade 7 Guitar Repertoire.

My sheet music is based on a number of different sources. Most of the fingering is similar to that presented in the RCM Classical Guitar Repertoire and Etudes 7.

All notes are the same, with the exception of the bass F in measure 15, which I have moved up an octave to avoid the awkward 1st to 5th fret stretch with a barre necessitated by playing the note in its original register.

The version of BWV 999 in the RCM Classical Guitar Repertoire and Studies changes the quarter notes and rests of the original to half notes. In my version, I opted to make the bass notes quarter notes, as in the original.